Perhaps the most difficult race in track & field is the 400-meter, or quarter-mile. It requires a combination of speed and endurance that pushes the human body to its physical limitations. There also is a psychological component. Competitors do not ease into the 400-meter. They achieve full speed as quickly as possible and then push through the pain to maintain their pace.

Perhaps the most difficult race in track & field is the 400-meter, or quarter-mile. It requires a combination of speed and endurance that pushes the human body to its physical limitations. There also is a psychological component. Competitors do not ease into the 400-meter. They achieve full speed as quickly as possible and then push through the pain to maintain their pace.

Given the demands of the 400, it’s no surprise that retired Vice Admiral James Sagerholm chose it as his signature race as a track athlete in high school—though back then the distance was 440 yards, before the metric system took over track & field in 1979. In turn, one memorable meet convinced him to join the military. A BGES member for more than a decade, Sagerholm went on to serve his country with honor and distinction for 33 years. During that time, he learned the meaning of true leadership and how it can motivate people to do great things.

“My experience tells me there are five bedrock principles,” says Sagerholm. “Know your people. Trust your people. Let your people do their jobs. Stand with your people at all times. And be consistent in whatever you do. Put all those together, and you have an effective leader.”

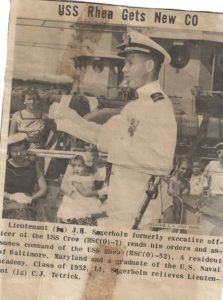

Sagerholm got his first exposure to dynamic leadership during the Korean War on board the USS Rochester under the command of the legendary Richard H. Phillips. He later served on minesweepers and destroyers, and also commanded a ballistic missile submarine for three years. In 1975, Sagerholm was promoted to rear admiral. He worked at the Pentagon, and then took command of the South Atlantic Force (now the U.S. Fourth Fleet). Sagerholm next spent a year in the White House as director of President Ronald Reagan’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board. In 1983, he was appointed vice admiral and served three years as Chief of Naval Education and Training. He retired from the Navy in 1985.

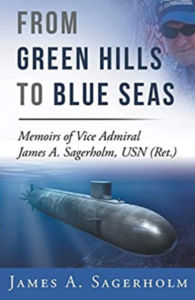

Sagerholm’s career often gave him a front-row seat to historic change in the U.S. Sometimes he was even the author of it. In 1952, for instance, he helped create the honor system for the Naval Academy. Along the way, he made his fair share of famous friends and reported to more than a few storied figures. He recounted his life’s adventures in his 2015 autobiography, From Green Hills to Blue Seas.

Those green hills were located in southwestern Pennsylvania. Sagerholm was born in Uniontown in 1927, a birthplace he shares with George Marshall, the 15th Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army. Sagerholm still remembers attending the town’s Memorial Day Parade as a seven-year-old. “I was there with my brother and father,” he says. “I saluted a small group of old men in blue uniforms, and they returned it. I was thrilled.”

That brief encounter helped spark a lifelong passion for military history. His fascination grew in the summer of 1941, during a Boy Scout retreat, when Sagerholm was part of an archaeological dig near Fort Necessity where Gen. Edward Braddock is buried. “Initially, we found nothing,” he says. “Then suddenly we came upon bullets, buttons, and sword parts. That ignited my imagination.”

Sagerholm’s interest was further piqued after his family moved to Baltimore in 1942, after the attack on Pearl Harbor. His father was an accountant and saw a way to help the war effort by working for aircraft manufacturer Glenn L. Martin. A short time after Sagerholm headed east, the family took a trip to Gettysburg. “That sealed the deal for me,” says Sagerholm.

Meanwhile, he was becoming a track star at Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, establishing himself as a force in the 440. It was a meet against plebes at the U.S. Naval Academy that swayed him to pursue the military as a career. “I was very impressed with the Academy,” Sagerholm recalls. “At that moment, I resolved to be a midshipman.”

Meanwhile, he was becoming a track star at Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, establishing himself as a force in the 440. It was a meet against plebes at the U.S. Naval Academy that swayed him to pursue the military as a career. “I was very impressed with the Academy,” Sagerholm recalls. “At that moment, I resolved to be a midshipman.”

Sagerholm enlisted in the Navy in 1946 and eventually rose to the level of aerographer’s mate, serving at the Navy Hurricane Weather Central in Miami. Finally, in 1948, he got the news he had been waiting for—an appointment to the Naval Academy. He made his mark immediately, including being elected his class president. That put Sagerholm in a position of great influence.

“Unlike West Point, at the time Annapolis did not have an Honor Code that formally defined “Honor,” says Sagerholm. “Although it was understood somewhat that lying, cheating, and stealing, for example, were major offenses and violations of personal honor.”

Vice Admiral Harry W. Hill, the architect of the Pacific Fleet’s amphibious operations in World War II, was the Superintendent of the Naval Academy from 1949 to August 1952. During his tenure, Hill met monthly with the three incumbent class presidents (the plebe class does not have a class organization). The group consisted of Sagerholm, the Class of 1951’s Bill Lawrence, and the Class of 1953’s Ross Perot.

“In our discussions with the Supe, we concluded that we needed something that formally addressed honor,” says Sagerholm. “We found West Point and other school codes to be too arbitrary, so we constructed the Honor Concept that includes remediation when it is evident that the accused was ignorant of or confused about the concept of honor. Ultimately, we came up with the system that’s still in existence today.”

That proved a tremendous springboard for Sagerholm’s career. In the years and decades that followed, he consistently worked his way up the ranks of the Navy. In the process, he learned a lot about leadership. Rear Admiral Phillips made the biggest impression on him. “He was the best commander I ever served under,” says Sagerholm.

Sagerholm’s lifelong study of the Civil War has provided critical insight into what makes a great leader as well. It also taught him the need to preserve American history as a means to educate younger generations. That’s partly why he is an ardent supporter of the American Battlefield Trust and BGES.

“We cannot really understand the current issues in America without knowing their origin,” he says. “For many of them a study of the Civil War and its causes is required. But war means battles, and the study of war cannot be done adequately without including the battles and the acts of men therein. Battles cannot be adequately comprehended without studying the grounds where the battles took place. Thus, the need for the preservation of battlefields becomes obvious.

“Visiting the sites where men struggled and died in defense of the ideals that have been the hallmark of America, and have made our beloved nation the bright beacon of freedom in this world,” he adds. “Absent this knowledge, the leaders of tomorrow will be handicapped in keeping America on the right course.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.